Written by Juan Pablo Iñamagua-Uyaguari, University of Aberdeen

Using Drones to Study Livestock and Trees in Ecuador – a Travel Report from Field Work.

Photo above: Tree measurements. Manabí province, Coastal region.

In the COP 21, leaders of the world agreed on actions to reduce climate change. This worldwide commitment was seen as a victory that will help to decarbonize the economy in order to achieve a [sustainable] future. To keep global warming below 2°C, a reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is needed, but also negative emissions (carbon dioxide removal) are required as a strategy to achieve this planetary goal. Worldwide, livestock systems are one of the main contributors to GHG emissions to the atmosphere, predominantly due to methane emissions from enteric fermentation, produced as a by-product of the cattle metabolism. Whilst most of the past research on climate change mitigation in livestock systems focused on emissions reduction, livestock systems can also contribute to negative emissions through increasing the carbon removal from the atmosphere. Increased carbon removal could be obtained by soil and pasture management or the incorporation of trees in the production systems. Livestock systems in the tropical countries are characterized by lower productivity in comparison with those located on subtropical and temperate regions.

Photo: Typical landscape dominated by pasture areas. Napo province, Amazon region.

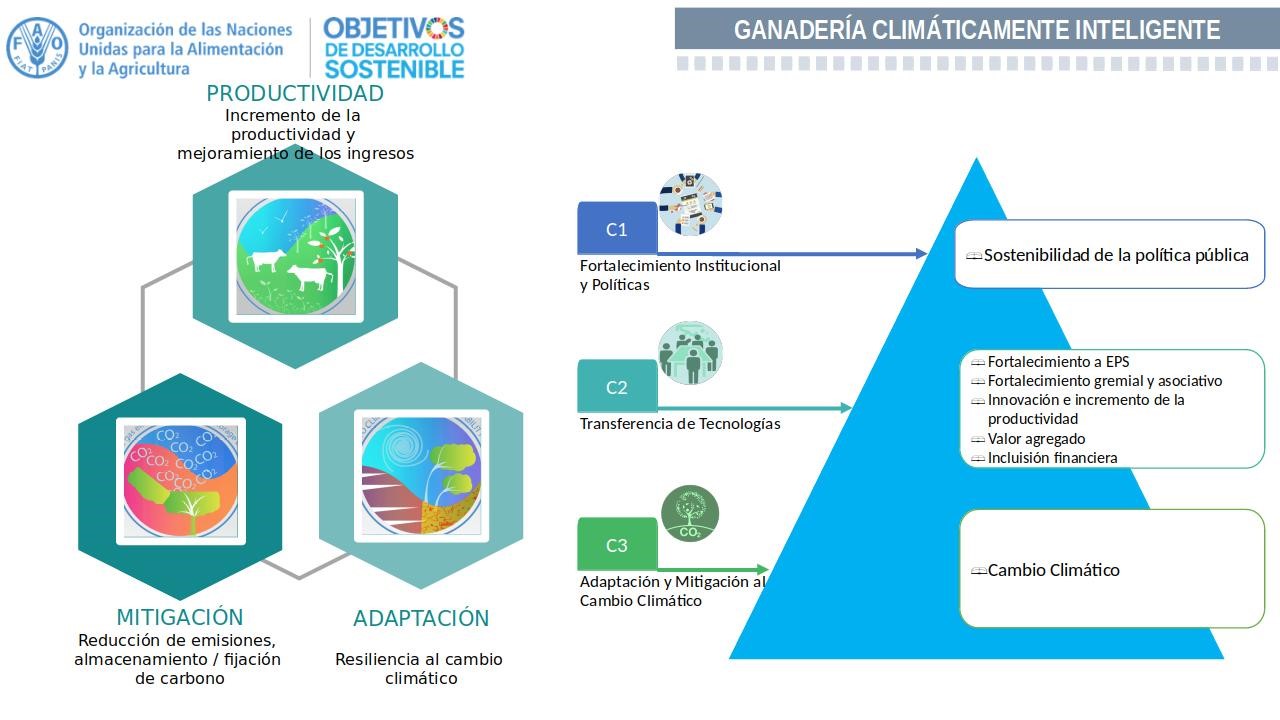

During the last 10 months, I have been studying trees in livestock farms in the Coastal and Amazon region in Ecuador, my home country. The farms are part of the Climate Smart Livestock project, managed by the FAO office in Ecuador. The project goals are to identify and apply smart management strategies that can contribute to increase productivity, reduce GHG emissions from the farm livestock activities and to increase the resilience to climate change.

Figure: Climate Smart Livestock Project goals. Source: “Proyecto Ganadería Climáticamente Inteligente”, FAO-Ecuador

Since usually the contribution of trees outside forests are not considered in the national inventories , this project focused entirely on the presence of trees on pasture areas. The objective was to quantify in which extent trees on pastures contribute to negative emissions, through the carbon stored in the aboveground biomass of these trees. For quantifying tree biomass we installed plots (sampling areas) at each farm representative of the total pasture areas of the farms. These areas were recommended by the farm owners. In each plot (1000 m2) we measured and recorded tree species and characteristics, such as height, diameter at breast height and canopy diameter.

Photo: Drone survey in a pasture area. Guayas province, Coastal region

Measuring trees at the ground can be a challenging and demanding activity, especially in terms of labour hours, which limits the size of the study area. To overcome this limitation, we used a drone (an Unnamed Aerial Vehicle), to take aerial photography from the areas surrounding the main plot area in order to cover a larger area. The drone survey covered an area 50 times bigger than the original plot. Using photogrammetry techniques, we will be able to extract from the drone photography the same information that was extracted from field measurements, such as height and altitude. We will then use this to estimate the amount of carbon stored on the woody aboveground biomass in livestock systems.

Photo: Aerial photography in pasture areas. Morona Santiago province, Amazon region

Using drones allows not just to increase the size of the study area, but will also help us to understand the spatial arrangements of trees on pastures. Identifying the most common spatial arrangements in each region, and using this information for silvopastoril technology transfer programs, could help to increase the adoption rate of this practices, and consequently the climate change mitigation from this production systems.

Photo: At 1900m.a.s.l the fog is very common and made difficult to complete the drone survey. Morona Santiago, Amazon region.

The field work phase has been an incredible experience, not only from a scientific perspective, but also from a personal perspective. I was able to witness and [to some extent] experience the conditions in which farmers carry out their activities. In a country characterized by its rich biodiversity and also by its social inequality, small and medium livestock farmers an indigenous communities are the guardians of biodiversity and the natural capital in the tropics.

Photo: Farmer and his family planting trees on pasture areas. Santa Elena province, Coastal region.

Is true that livestock is one of the main drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss, but in many cases, practices that lead to deforestation are used as the last and only resource that farmers have to make some money to support the basic needs of their families. To achieve nature conservation and social and economical development in developing regions is still a challenge that has to be addressed. Incorporating trees on production systems will not only have positive impacts in terms of biodiversity conservation, but also can contribute to the family economy, due to the commercialization of fruits, fibres, timber. Sustainable practices adoption in developing regions need to be considered as a priority and a key strategy to improve the well-being of society and to contribute to climate change mitigation.

Think global, act local, plant some trees!

I am very thankful with IRSAE for its financial support to travel from Aberdeen to Ecuador. Also with the FAO Climate Smart Livestock project team, for their tremendous support on the field during the last 10 months.

Photo: The crew